Comparison of a Normal Knee and an Osteoarthritic Knee

Reproduced from Osteoarthritis, David J Hunter and David T Felson, BMJ 333, 639-642, 2006, with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common form of arthritis. It is a disease that affects all the tissues of the joint, including the cartilage, bone, ligaments, and muscles. It can develop in any number of joints, but most commonly affects the knees, hands, and hips. Osteoarthritis typically occurs later in life, usually after age 50, although may start earlier in the case of joint injury. The symptoms of OA can vary in severity, but in its more severe forms OA is a painful condition that restricts mobility, interrupts sleep, and interferes with the sufferer’s enjoyment of life. OA is considered a chronic (long-lasting) disease and other than joint replacement surgery there is presently no cure. There are, however, treatments that can reduce pain, improve function, and in some instances delay the progression of the disease.

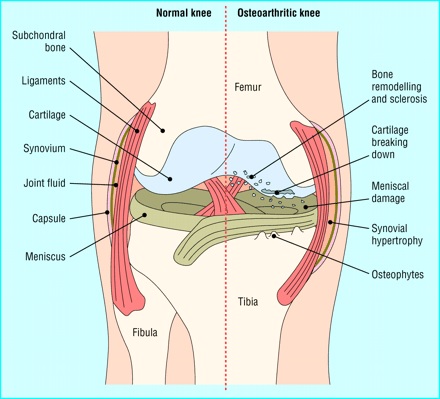

The progression of OA may be charted by comparing a normal healthy joint with an osteoarthritic joint. In a healthy joint, protective cartilage caps the ends of joint bones. Around the bones and cartilage is a further protective “wrapping” called the synovial membrane. This membrane contains synovial fluid, the joint’s lubrication that allows cartilage-capped joint bones to glide smoothly for pain-free range of motion.

In contrast, a joint with osteoarthritis will have, to varying degrees:

- Damage to the joint’s cartilage as it becomes less elastic and more brittle

- Bony spurs growing around the edge of the joint

- Swelling of the joint due to inflammation

- Inadequate lubricating synovial fluid for the cartilage and joint bones

- Breakdown of ligaments (tough bands that hold the joint together) and tendons (cords attaching muscles to bones).

Early in the disease process, the body has resources to repair detrimental changes within an OA joint. As the disease progresses, the body’s repair system can no longer keep up with these processes, resulting in the tissue damage that is called “osteoarthritis”. It is important to note, however, that OA does not necessarily progress to more severe disease and that a significant number of people experience no progression or even improvement. Furthermore, the structural changes seen in the joint on an x-ray do not correspond well to the symptoms that you feel. In some cases, the structural changes may be severe but the person feels very little pain.

Lay version of the OARSI definition of osteoarthritis

“Osteoarthritis is a disorder that can affect any moveable joint of the body, for example knees, hips, and hands. It can show itself as a breakdown of tissues and abnormal changes to cell structures of joints, which can be initiated by injury. As the joint tries to repair, it can lead to other problems.

Osteoarthritis first shows itself as a change to the biological processes within a joint, followed by abnormal changes to the joint, such as the breakdown of cartilage, bone reshaping, bony lumps, joint inflammation, and loss of joint function. This can result in pain, stiffness and loss of movement. There are certain factors which make some people more vulnerable to developing osteoarthritis, such as genetic factors, other joint disorders (such as rheumatoid arthritis), injury to the joint from accidents or surgery, being overweight or doing heavy physical activity in some sports or a person’s job”.

Research User Group, Institute of Primary Care and Health Sciences, Keele University, UK